Fieldwork at the Arboretum: « Vegetal Companions: Arts, Sciences and Temporalities of Co-Existence »

»Vegetal Companions« is a collaboration of Späth Aboretum with the Cluster of Excellence »Matters of Activity« at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin as part of the _matter Festival 2025.

A wonderful springtime evening in the outskirt of Berlin: the project team of Vegetal Companions invited the « Matters of Activity » Cluster members for the opening of evening: Planted Archive.

»Vegetal Companions« is a collaboration of Späth Aboretum with the Cluster of Excellence »Matters of Activity« at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin as part of the _matter Festival 2025.

Project Lead, Concept and Curation »Vegetal Companions«: Robert Stock and Rahel Kesselring

With support of: Maja Avnat

Project Lead Späth Arboretum: Anika Dreilich

Festival Contributions: Maja Avnat, Johanna Hehemeyer-Cürten, Rahel Kesselring, Emma Sicher

Technical Assistance: Alexander Struck, Martin Wagner

Event Assistance: Maria Pape

Infrastructuring the multimodal: Workshop at the University of Cambridge

Caroline is singing us a song. And then in the end she asked us to sing together for ourselves. Not to save anyone’s soul, just to feel how it is to be in the song mode.

For two days, Iza Kavedžija, Liana Chua, and Natalia Buitron brought a group of inventive ethnographers from across Europe to the Center for Research on the Arts, Social Sciences and Humanities. They invited us to three panels — visual, sonic, and literary practices — for a conversation around the future of multimodal ethnography. How can we value and evaluate academic works that operate at the border with artful practices? How can we accommodate unusual academic outputs in a journal such as the Cambridge Anthropology Journal?

The workshop was strongly reminiscent of a project conducted by three of my colleagues at the Humboldt University. Iza opened her introduction with an acknowledgement of this earlier project, which bears the same subtitle: “Evaluating multimodal forms.” I know these colleagues well. I co-taught multimodal ethnography with two of them in recent years. Back in Berlin that same week, I met with Andrew Gilbert and Ignacio Farias. They were a bit perplexed by the workshop in Cambridge. They were surprised they weren’t invited to that Cambridge gathering —but it’s just that the word hadn’t gone around yet. These things happen. Tomas, Ignacio and Andrew have just completed a manuscript of their toolkit for multimodal appreciation, which they are submitting to the multimodal section of the American Anthropologist journal.

It is significant that we met to evaluate two master's theses, getting the students through their defences. Both students were very inspired by the multimodal ethnography teaching. Max did the ethnography of a VR project related to ageing. Alexander got started with fermentation workshops and went on to develop a thesis on fungal biohacking communities in Berlin. Both of them could have used multimodal material in their thesis. Yet they made only use of text, though, in a rather straightforward academic way. Not that the guidelines are especially rigid. It just doesn’t pay extra to go that extra mile, and the students seem to be acutely aware of it.

It doesn’t seem to pay more to go the extra mile in professional academic ethnography either. And this was at the core of the conversations we had during these two days in Cambridge. The extra work is not accounted for in the point systems of the neoliberal university. So why do anthropologists, like the group that was gathered in Cambridge that day, keep pushing that border? Two arguments came up a lot. 1) Other media and mediations make us see and feel things differently, and the ethnographic media can be integral to the ethnographic argument. 2) Making ethnography different is fun and keeps us alive. These two things, of course, go together. But aren’t these two arguments applicable to any good ethnography today? That’s the question I asked Julia Offen, the editor of anthropology and humanism, and the main invited provocation on the literary panel. So there is the boring stuff on one hand and the good, creative stuff on the other hand? Wasn’t ethnography always multimodal? In short, yes, replied Julia. Until the discipline weighted itself down with value criteria derived from big science to justify its existence (and its funding).

American Anthropologist was the first journal to get a multimodal section going. Andrew, as well as his colleagues of the “Multimodal Appreciation” project in Berlin, aren’t convinced that having a separate section for multimodal work is the way to go. The term will die, Andrew tells me over coffee, because it will be absorbed by the field of anthropology again. He quotes (loosely but precisely) a sentence from the last editorial of the Entanglement journal, a multimodal venue that closed shop in 2022: “This rush to tell the story of multimodal ethnography, to stake a claim and to define, feels really premature; it forecloses, it feels to us, experimentation which is at the heart of multimodality.” (1)

So maybe it’s not about staking a claim at all. Not about carving out new territories or formalising yet another sub-discipline. Maybe it’s about resisting that very impulse — the impulse to fix, to define, to institutionalise too early. Maybe it’s about staying with the looseness, the makeshift, the experimental — not because it’s easier (it’s not), but because that’s where ethnography comes alive. In the tentative, the collaborative, the not-yet-named. What if the point is not to assert what multimodal ethnography is, but to keep asking what it can be? Maybe it’s about holding open space for that singing-together moment — not to save anyone’s soul, but just to be, for a while, in the mode of the song.

(1) Nolas, M., Varvantakis, C., Long, R., Walton, E., and Logan, B. (2022). Last but not least, entanglements, 5(1): 1-7

Fieldwork overstretch

This is a drawing of my wife about to give birth to our twins, last August. I noticed immediately that something was off with this endeavour —not the birth, but the idea of drawing through it. The notebook I had picked (I wanted it to be analogue this time) didn’t absorb the water correctly. Matter was trying to tell me something. Drawing wouldn’t cut through this one.

Maybe I’m sometimes using drawing to retreat from the situation I’m participating in. Useful sometimes. Usually, it actually works in the opposite way, as a form of participation. Maybe that’s what I was aiming at. C-section is letting the partner on the side even more that a vaginal birth (my wife has trained me not to call it unnatural —she’s the pro.) I thought I would keep a trace of it all.

Weirdly enough, my children decided to come into the world in the very same building where I have been conducting my last five years of fieldwork. The freshly renovated high tower of the Charité has a similar floor plan on every floor. The neonatology unit looks exactly like the neurosurgery station, 7 storeys higher. Very different clientele, I noted, didn’t need to be a trained ethnologist for that. The impression stuck with me: we were giving birth at my place of work. I could even sleep there, but I haven’t done it before.

The next moment after that painting, my wife got into the necessary prep for the surgery — that surgery was something we had not invited but had to be in this special case, through multiple factors scripted in ways that seem, even after the deed, just what had to be.

As I stepped in the room, she was already out of reach. Drawing seemed futile at this point, as someone was going with a knife through the skin and muscles of the love of my life. The obstetrician was actually super nice and sovereign, a woman who immediately inspired confidence as she admitted us barely an hour prior to this scene. We had been reallocated. The neonatology department was short of a slot at the other place. Then I was sitting there, and I remember my mechanical pencil fell on the floor from my pocket. The doctor was startled at the clicking noise and looked for the source of the foreign sound. I mumbled excuses and I sat on my notebook, very literally so, on the tiny black hooker.

Things went as well as they reasonably could. The tiny boys were in good shape, one of them slim, very slim, the other one a big baby. Sound and safe, all of them. After a few days, they were almost wireless. I kept running into colleagues in the elevator during the ten days we spent at the hospital.

We liked the staff. They liked us, too. They let us go home early. That was good for our 5-year-old, who was amazingly patient with us and with his grandmother, who flew in from France to attend to him.

So yes, I don’t have much to show for my intended piece of contemporary ethnography — it may be true that anthropologists attend to whatever we do in an ethnographic way. But, more often than not, isn’t fieldwork just about being there? The paper doesn’t always absorb presence. The vastly superior absorbing power of diapers had the final answer.

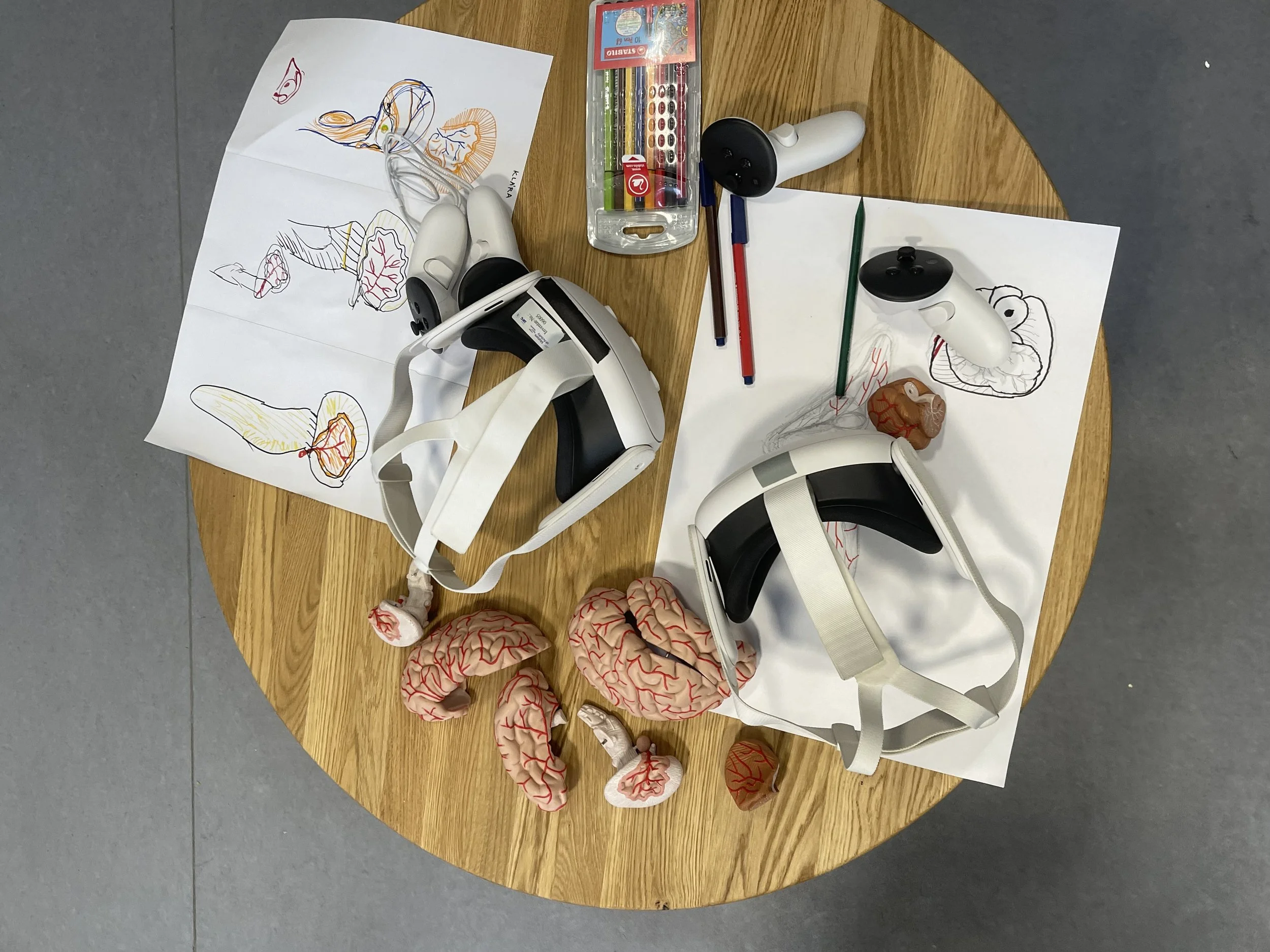

3D sketching participative performances as fieldwork

Our first "More-than-human Sketching" series event was a great success! Not only were the workshops fully booked, but the SpecLab team also spent two days developing a new immersive performance for the museum's visitors using augmented reality glasses and spatial drawing software. The performance, "Drawing as Digestion: Spatial Knowing Processes," will be presented to the public soon (dates will be announced on the Berlin State Museums' website). Short lectures and activities by Elaine Bonavia, Paulina Greta Stefanovic, and myself provided an unusual framework for participants to engage with the embodied and transformative power of tracing lines and being traced by them.

The "More-than-human Sketching" series aims to repurpose an emerging digital design tool, 3D drawing, to relate to collection objects. This tool is currently used by the Speculative Realities Lab (Cluster of Excellence »Matters of Activity« / Department for Neurosurgery, Charité) to suggest new approaches to neuroanatomical teaching.

augmented coral at KGM ©MLC

Through these experimental performative scores, immersants (as we call the spectators of immersive performances) are invited to explore the “more-than-human” exhibition at KGM exhibition actively through collective engagements with spatial sketching (the exhibition is also featuring the fabulous work with artificial coral gardens of Cluster Member Rasa Weber.)

Don't miss the next workshop, "Knitting of Crafted Things: Digitizing Worlds in Textile Networks," which will take place at the Kunstgewerbemuseum Berlin on June 20-21. During this workshop, a second performance will be created, this time in collaboration with another SpecLab member, textile designer Nayeli Vega.

Micro Phenomenology Crash Course. Practical Tips and Tricks for Fieldwork with First-Person Experience

As the latecomers entered the room of the workshop that morning at the cluster “Matters of Activity”, they encountered yet another head-scratching scene. In small groups, the participants were silently enjoying some collaborative stone gardening. Kat Heimann, our instructor from Aarhus University, was moving deftly from table to table, making sure we were diving into her “stoning game,” as she called it. After a little while, she asked our little group: what was a moment that especially surprised you?

The Micro-Phenomenology Crash Course from Feb 7 to 9, 2024 focused on collecting lived experiences through a specific interview method. Organized by Zeynep Akbal and myself at MoA, the workshop featured the exploration of two VR pieces from the Stretching Senses School project: “Subterranean Matters” and the “Virtual Sensing Knife.” Read the full ethnographic story there.

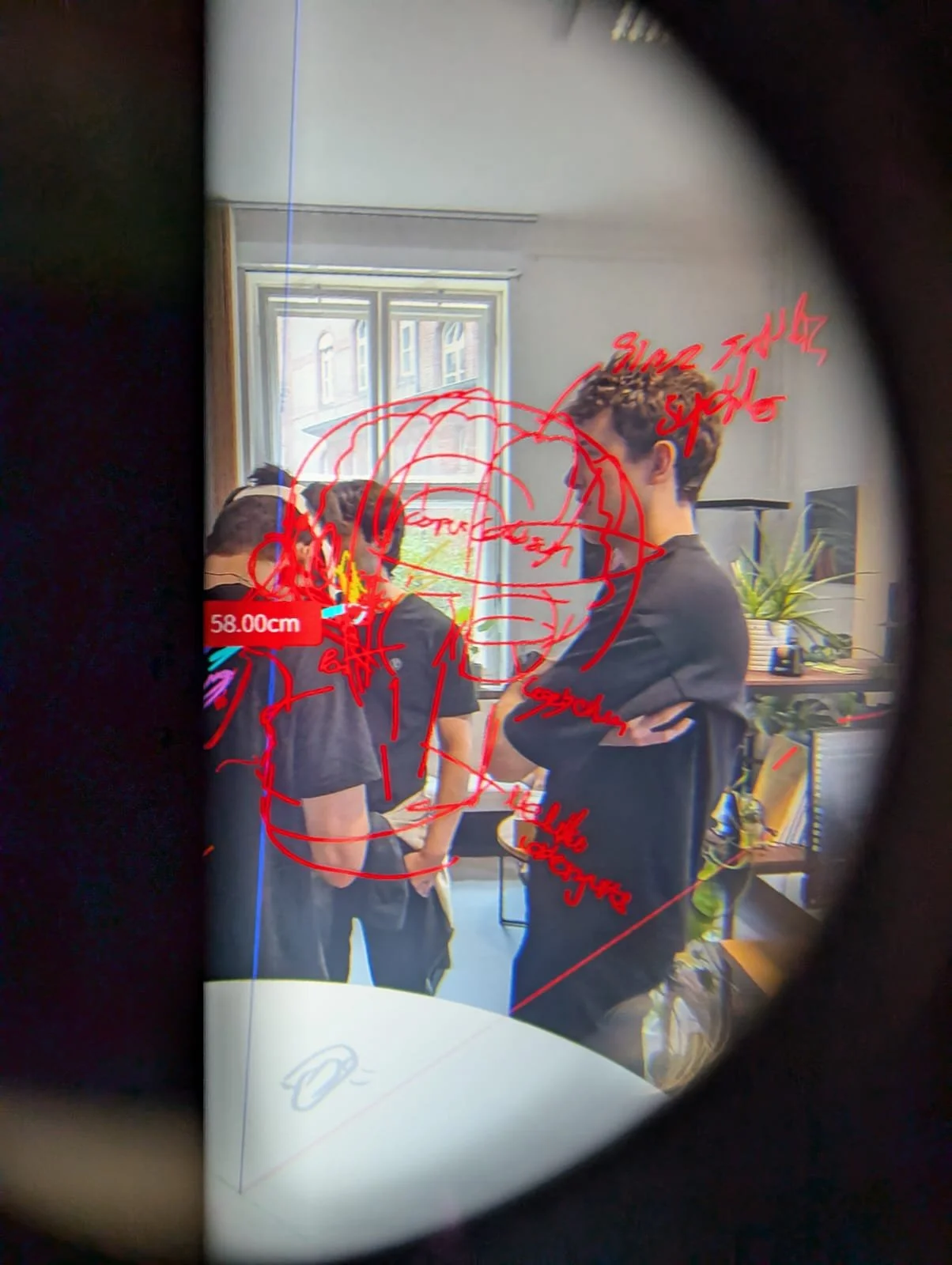

Rubbing as fieldwork: Workshop on site writing with technologies of captures, with MELT, Shauna Janssen and the Speculative Realities Lab at Kunstgewerbemuseum

Last week, in collaboration with the SpecLab, I had the privilege of inviting MELT (Ren Loren Britton + Iz Paehr) and Shauna Janssen from Concordia University for a three-day workshop/gathering at the Kunstgewerbemuseum, with Claudia Banz as our host. The vibrant group of participants and the museum's cosy atmosphere created a splendid contrast against its spacious and brutalist architecture.

Ren and Iz led the morning sessions, while Shauna unfortunately had to remain at home. However, her insights on “Site Writing” continued to resonate with us throughout the workshop. In the afternoons, the SpecLab team presented multiple resources related to our ongoing research on brain data navigation at Charité. The focal point of this presentation was the early-stage prototype itself, which can be seen in the image above, as neuroscientist Melina Engelhardt interacts with the data.

MELT introduced us to their tools, such as the Collective Conditions, an exercise called "Warming Up to Theory," in which we danced several texts that they had selected, and the "Rituals Against Barriers."

On the first day, we used "frottage" to connect with the area around us. Inspired by Shauna's guidance, we continued with "frottage" and rubbings using technologies like Lidar and photogrammetry scanning apps. This allowed us to rub objects that are usually kept behind glass, like those in display cases. We imported these rubbings into mixed reality glasses and continued rubbing with them.

On the second day, after speaking with neurosurgeon Thomas Picht and our colleagues from the Image Guidance Lab at Charité, we started thinking about brain data and our neurosurgical case study in terms of rubbing. How can we effectively rub with the spatial information to better understand it? We had a productive and relaxing time, and we're eagerly anticipating our next workshops at the Kunstgewerbemuseum. We'll be exploring how to engage visitors with the material processes and the enjoyable work of craft people through immersive installations and score. Stay tuned for more on the "Quasi-Makers" series event at KGM.

Claudia, Lin & Ren enjoying the results of the rubbing during the final public workshop session on the Friday afternoon.

Neuroscientists Melina Engelhardt and Robert Schenk grasping for brain tracts in our prototype at KGM, assisted by creative coder Warja Rybakova ©Maxime Le Calvé

The visiting scholar as ethnographer: fieldwork at the University of Oxford

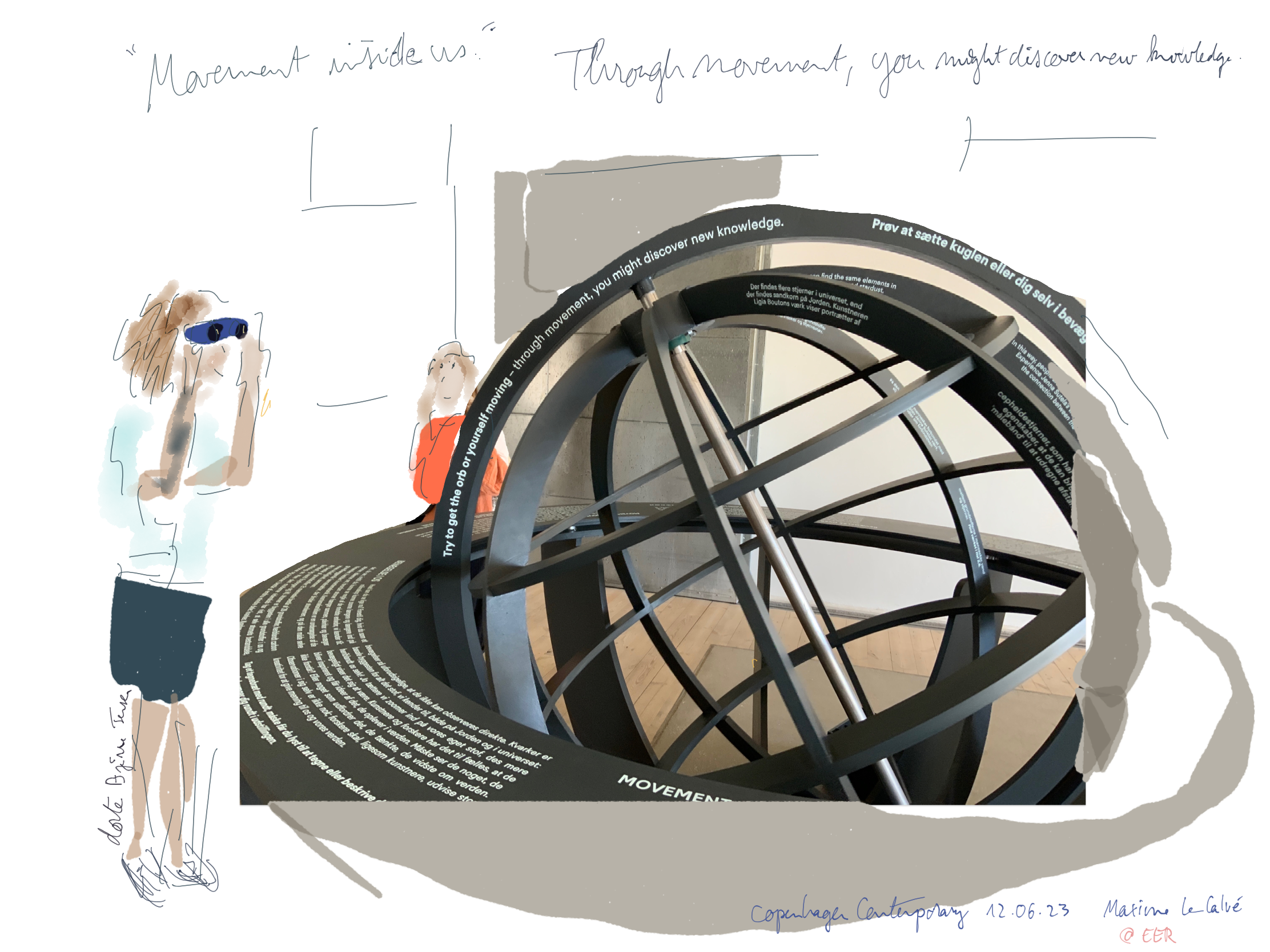

Fieldworking art-science: a tour of the “Yet, it moves!” exhibition at Copenhagen Contemporary with EER

Two weeks ago, I was invited in Copenhagen by the EER project (Experimenting, Experiencing, Reflecting; Olafur Eliasson Studio + Interacting Mind Center at Aarhus University) to conduct a graphic ethnographic intervention at an idea-seeding experimental workshop. Our stay there started with a tour of the newly opened “Yet, it moves!” exhibition at Copenhagen Contemporary, an ambitious art-science project that a number of EER members helped develop, curated by fantastic curator Irene Campolmi, featuring the work of the fabulous Helene Nymann, and the wizard anthropologist Joe Dumit working his good spells in the background.

In a low-key synchronicity event prefiguring some of the motion-driven mystics of the afternoon’s theme, I bumped into my new colleagues on the bus to the exhibition after a difficult train trip. The exhibition space opened recently at an ancient shipyard at the end of the bus lines. Crowds were converging there for CopenHell, a festival for heavy metal lovers. Curator Irene Campolmi opened with a line by Galileo, using a famous sentence of his as a lever, catapulting us instantly to speed: “The earth is in the center of the universe, and yet it moves!” The show brings the visitors to an estranging encounter with the perception worlds of modern science, stretching from the cosmos to the brain and back. At the tip of the artists’ fingers, science data and imaginations of matter commit with each other into cosmic assemblages. They all usher us onto a moving map of what we are in their various ways. The movement of the world – and us in it – becomes the foundation of purpose and cause, cutting together apart the lab and the studio. On the left of the sketch, one can see the piece Helene Nymann created for the show: a sculpture on a pink podium adorned with a QR code etched on brass; a video, and an inquiring web device. That work wants the visitors to remember what to remember. Their remembrances are then located on the “carte de tendre.”

There is a heavy orb in the lobby that moves smoothly. Try and set it in motion: the model of the world becomes an empty form that takes meaning only through the dynamic flows of perspective it enables. “Try to get the orb or yourself moving – through movement, you might discover new knowledge.” The pulsations inside us are brought in direct continuity with the vibrance of the universe. Dorte reaches for the binoculars and sets her gaze in motion – a shivering focus can bring things to dance again.

Datastreams flood through us in the ultra-high-definition audio-video installation of Ryoji Ikeda. The piece Dataverse is displayed in a huge room on three panes, three acts of a spacetime opera shown simultaneously with bombastic data sound triggering macroscopic unfoldings of picture matters throughout cosmos bodies. The feeling of awe turned us momentaneously into a Wagnerian audience process, sitting on the hard floor in the dark. A few members of EER, more inclined to keep moving, probed the work very close up, meeting with the pixels and disrupting the illusion.

The next piece was also monumental as a projection of monumental proportions. It showed us the inside of a glacier’s “throat” shortly before its collapse. Jakob Kudsk Steensen scanned the mighty being and presents video footage, points, and meshes, juxtaposing them into an intricate inner landscape. “My parents were mountaineers,” a subtitle told us as the subwoofers hummed deep subglacial tones. Everything else was dark save for the doorstep to the next enlightening experience.

The next piece was the much expected carte de tendre “Futur Continuous” video poetic piece of Helene Nymann. “Maybe the future is a memory you can remember, something you don’t want to be repeated.” “It’s time to draw a new map.” Situating us into an emotion landscape was an innovation of a female writer in the 17th century: together with friends, they invented a way to place the itinerary of a love journey. Helene crops out the map with a generative AI to remember the future of our human voyage. She stages herself and others into a dark loving affair with our grim perspectives and what we will leave ahead of us. What we will remember of the future. “Try to remember how your memory will make the future feel.”

The last piece of the show is a thinking bowl. The “Brain Pond” by Jenna Sutela is inviting the visitors to touch its rims and the water is keeps. A microphone picks the sound of it, mixed with sounds of prior interactions and whales and cosmos. The sound is not as “live” as the intrically written concept announces it, which makes the piece if yet interactive perhaps more uniformoulsy evocative of cosmic ripples and neural sparks. Kids love to touch its ears, Irene tells us, and we touched and tried to get the heavy brass bowl to sing.

“Yet, it moves!” points at the rich experiential world of science. Movement is one of the ways It is be deeply erroneous to think science worlds as disenchanted and waiting for the intervention of the artist or humanity scholar to reenchant them, as Natasha Myers points out in her ethnographic notes on how biologists encounter plant-sensing (2015). Much like the popular physics writing on quantum in the 1980s and 1990s, this exhibition pays attention to the emergence of new contemporary languages to articulate mystic experiences between science and art, into slightly grim future that still believe in human potential.

Writing Fieldwork with Chat-GPT: An Ethnographic Report "in the style of Anton Chekhov"

“I saw everything, so it is not a question of what I saw, but how I saw.” Anton Chekhov, Letter to Alexei Suvorin, SS Baikal, Tartar Strait,September 11, 1890 (2008)

I present here a series of graphic field notes drawn on site during the 'Driving the Human' event at the Cluster of Excellence “Matters of Activity” on May 10, 2023, along with ethnographic text co-written with ChatGPT. One of my favorite books on ethnographic writing practice suggests that the best companion for writing ethnography would be Anton Chekhov, who in his pioneering work on Sakhalin Island intended to write with “scientific and literary purposes in mind”. (Narayan 2012 : 3) Using an AI and prompting it to write 'in the style of Anton Chekhov' made me feel like I was partnering up with the great playwright —or almost so. Sometimes I had to edit a lot, sometimes I had to let in a few sentences that clearly showed that a non-human intelligence was at work. Chekhov would approve this mode of sketching things up, as shows this excerpt from a letter to his brother in 1899: “Don’t smooth out the rough edges, don’t polish; be clumsy and bold. Brevity is the sister of talent.”(2008) If the accidental lyricism of the IA works well with this motto, it also plays around a current limit that the Russian writer also recognized as his: As he wrote to a friend in another letter dating from 1897, uncannily relating to the state of ChatGPT at the moment: “My sins are unintentional because, as I am only now beginning to understand, I do not yet know how to write longer pieces.”(2008) Together with my drawings, the "taste of the hand" and the flavor of the AI combine to create — I hope— a reading experience as joyful as its making.

Read the essay there: https://stretchingmaterialities.pubpub.org/pub/ds0pgumg

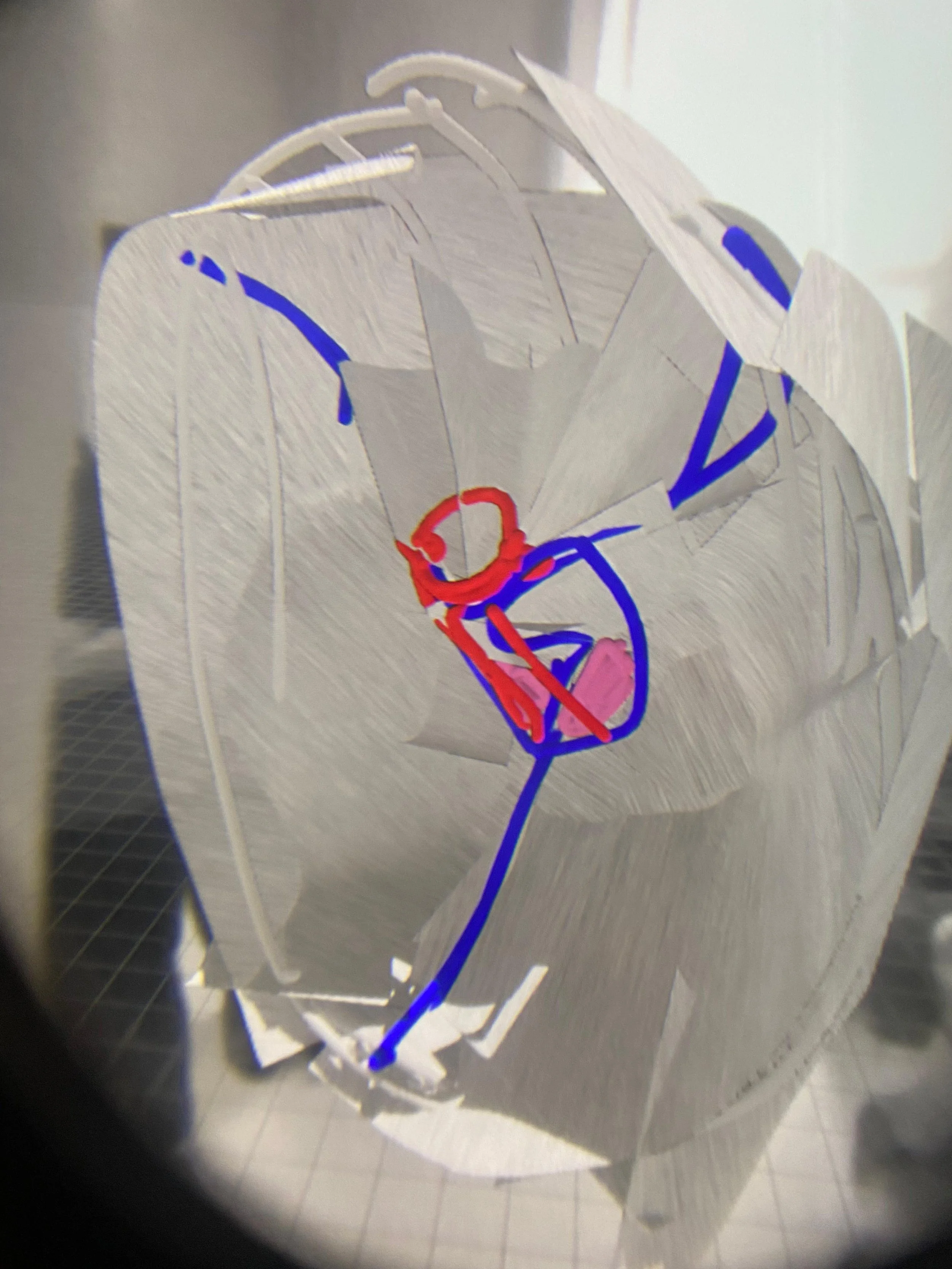

Conducting a 3D sketching workshop as fieldwork: Drawing and telling neuroanatomical landmarks spatially at the Speculative Realities Lab, Charité Berlin

How does the sense of space, and the haptic creativity associated with it, affect the teaching of anatomical knowledge? How can current practices be explored by shifting them to other techniques? In this first workshop of the SpecLab, together with HCI scholar Paulina Greta Stefanovic and neurosurgeon Thomas Picht, we challenged a group of participants from neurology, neuroscience, computer science, clinical linguistics, design and art to tell us "anatomical stories" using a 3D sketching tool. After a short introduction to the research project and a short tutorial, the participants jumped into the 3D sketching action using the free program Gravity Sketch.

The technological infrastructure was difficult to deal with at first, but with some inventive ways of overcoming a problematic internet connection, we were able to have participants share virtual rooms while moving around the same physical space. The new SpecLab space is a perfect playground for collaborative 3D sketching interactions. We hope to keep it as empty and spacious as possible. With the pass-through technology of the newer standalone headsets, we didn't have to worry about collisions. This gave the typical virtual reality technology a hint of what augmented reality might look like: the user is no longer alone, secluded in the headset. A wide range of shapes and materials were tried out that day, from arterial visualisations to images of neural forests and cartoon characters.

The last part of the workshop was a "hot seat" situation without a seat: several participants volunteered to tell us the stories they had created in the 3D sketching tool. Cathy, the first participant who took the floor, started with the sketch she had made: a view of the cortex and a sketch of the hypothalamus. She explained the manipulation she is currently doing in the lab, as part of a team working on the treatment of epilepsy. I then asked her to do it again, this time sketching the story 'live' as she went through the same narrative sequence. After a little hesitation ("it wouldn't be optimal"), she responded beautifully to the challenge and sketched the elements of her demonstration again in real time. That was fun! She seemed quite happy with her performance (despite an obvious preference for a cleaner 3D image that could be imported, she said). It was an exciting first result.

Next up was visual artist Vinh, a student at KHB Weissensee. He began by changing the scale with a majestic gesture: the previous cortex sketch became a small dot in 3D space, and he immediately began drawing a folded piece of paper in the air. "This," he told us enthusiastically, "is how I get students to engage with art in museums". The students start by folding a piece of paper, then draw a part of an image they like in the exhibition and pass it on to another person who continues the drawing without knowing the previous part. Vinh demonstrated how this works by drawing in this mode for a few minutes while talking about his pedagogical work in this context.

This was a very relevant conceptual contribution to the workshop, as we were discussing different ways of making learning processes more engaging through sketching techniques. I personally felt that he was still sketching in 2D - but he started using 3D extruded shapes and then it became really interesting. What if we introduced the use of 3D sketching for museum visits, we asked ourselves in the final discussion.

This shift from flat to spatial was an important theme throughout the session: participants described tricky anatomical structures in the brain that could not be guessed from 2D images (Thomas), or drew spatial representations of neurons from historical sources to illustrate a conversation about degenerative diseases (Wendy).

Some of the participants had to be "put on the spot" to perform in front of the audience. Linda, a student on the UdK Product Design Masters programme, happened to be particularly graphically eloquent with her 3D technique. She first announced an omelette, but seemed to change her mind at the start of the narrative sequence and ended up demonstrating how to cook an egg, sunny side up, "with ketchup". Linda was obviously more familiar with 3D tools: she made an egg with a brush that creates circular shapes, and asked us how to duplicate objects (she ended up sketching every single pan). This humorous final story said a lot about the nice atmosphere that the sketching activity had created in the group: an openness that is not always easy to emulate.

In the final discussion, we reflected on the different modalities of learning through sketching - for example, sketch mapping as a way of learning a cartographic representation by drawing it many times. Sketching can be a way to disrupt the perfectionist glow of the 3D material used in scientific imagery and bring the focus back to the performance itself and the many ways it brings people together.

Special thanks to Milena Burzlaff for the amazing support!

Note to self: on scaling way up ethnographic research into interdisciplinary reflections “beyond the normal procedure”

When my colleague anthropologist Laurence Douny landed a job at the cluster Matters of Activity, she probably didn’t expect her long-time research object on wild in West African silk would ignite the fantastic exhibition project DAOULA | sheen. Joined by Karin Krauthausen and Felix Sattler, team managed to go beyond the anthropological exhibition, beyond the way results are usually presented. They bridged convincingly anthropology, materials science, microbiology, design, cultural theory and curating (and as careful critical scholars, they made sure anthropology also reflected its approach). They brought together, using the exhibition as an adjacenting device, communities of silk weavers, imaging specialists and wordsmiths across continents. As Karin shared with me: “The idea of the exhibition project was to accompany the interdisciplinary research process on African materials and by doing so activate a space of reflection for each discipline to go beyond its normal procedures.” It is the paramount case of an exhibition-as-research that turned right, with engagement from every side, fascinating documentation from local video and audio artists, partnership with the local museum for a show on the spot. Karin again: “Four interview films of the South-African film maker Thabo Thindi and his composition of the film material from Burkina Faso (his ‚director’s cut‘ so to say) are at the center of the exhibition.”

The last months of the show are already upon us, and this tour came across as a deeply matured story on a social aesthetic phenomenon. “In Burkina Faso ›daoula‹ is a term meaning ›sheen‹ or ›charisma.‹” How do these women shine in society while communicating their emotions? How do craftspeople make deal with microbes to get them to dye the clothes? What do biofilms have to do with this traditional process? How can designer translate the work of caterpillars into onsite text sculptures using similar growth algorithms? How to bring the community to share their techniques while shining back on them the importance of endangered traditional everyday arts? Many more questions are asked and answered in this marvellously weaved exposition at Tieranatomisches Theater in Berlin. Sometimes, interdisciplinary is not just wishful thinking, and wisdom comes pouring out of these insightful constellations.

Special thanks for Karin Krauthausen for her comments on a previous version of this text, who made sure that I got it write: this is not an anthropological exhibition. It is much more than that.

Taking a break from/as fieldwork

Fieldwork in the art-science VR scene: Sophie Erlund & the Experimenting, Experiencing, Reflecting group @PSM Gallery

Yesterday at the PSM Gallery in Schöneberg (Berlin), Sophie Erlund was presenting half a day of workshop and presentations around her VR piece Nature is an event that never stops. She has been working on that piece for the last six months, and it will be on display until 25.02.2023. It’s fantastic, definitely worth a trip to this part of the city where a cluster of galleries is established, on the opposite side of the canal from the Neue Nationalgalerie.

The artwork is a collaboration with the EER group, a mixed bunch of scientists and artists interested in playful approaches to inquire into perception. They offer pathways between cognitive science and installation art, using a “French” method to conceive and evaluate these hybrid setups: microphenomenology. The cognitive scientist Katrin Heimann interviewed visitors and presented her first conclusions in the first part of the workshop in text-heavy slides. She invited us to close our eyes as she channeled the experiences “in first-person” that she had collected. In the second part, Karsten Olsen presented his work on “cultural transmission,” the cognitive mechanism that is explored in the piece by Sophie Erlund. How are sketches or colors transformed as they are memorized and transmitted?

Microphenomenology is the child of the philosopher Claire Petitmengin. The method is elaborating on a technique called the “elicitation interview” which was invented by Pierre Vermersch (1994) and further developed in collaboration with Nathalie Depraz and Francisco Varela as a “phenomenological practice” in the book On Becoming Aware: A pragmatics of experiencing (2003). It is a delicate practice, a deep dive of the interviewer and the interviewee into the sensations and thoughts that occurred during a targeted experience. Claire Petitmengin has conducted research in contemplative science for the last 30 years. The method she teaches indeed shares many principles with meditation, evolving self-inquiry into interpersonal approaches. The method came to me in a new light influenced by the work of EER member Joe Dumit: what if we took it as a contact improvisation exploration inside and around a phenomenon? That day, we centered the interpersonal perceptive field on the lived experience of unprepared visitors going through the VR “film” of Sophie Erlund.

The final panel featured the artists Sophie Erlund and Helene Nymann, the neuroscientist, poet, and brain activist Pireeni Sundaralingam, and the anthropologist and cognitive scientist Andreas Roepstorff. It was introduced by Helena Herzberg, the art manager of PSM Gallery. The session was touching on many topics ranging from cognitive flexibility in school kids to funding schemes for art-science endeavors. Excellent both in content and shape, this two-hour conversation strokes a powerful chord. The participants took the context of EER and the production of the VR piece as a start. The focus went quickly to the serious political implication of bringing together in playful ways the knowledge of cognitive neuroscience and that of artists. Challenged by the audience, speakers stated the urgency of encouraging resistance against the pervading rigidity of the educating system, as well as the uncertainty-adverse societal context. Staging and sharing more-than-human perceptions, as Erlund does so masterfully in her VR film, is one of the many ways to champion tender attention to other people's experiences. As the EER member and play scholar Amos Blanton puts it in the end: bringing children and adults into creative exercises brings up the fears of failing and coming short. Yet the moment when they become engaged in the aesthetic activity, these fears dissolve and the joy of tinkering takes over. Hearing these words, I lifted up my head from my iPad for a short moment, reflecting on graphic ethnography and my experience of teaching ethnography through drawing. So much food for thought today, and great insights on how to frame an art-science VR experience. The panel, as well as the other interventions of the day, were documented and will be available soon on https://www.eer.info/

All the info is on the website of the gallery.

Sharing my sketchy fieldnotes on the spot with anthropologist colleague Andreas Roepstorff w/ ©Yoonha Kim, exchanging first-person impressions in embodied way at the end of the day.

Teaching Digital Neurosurgery as Fieldwork: Mixed Reality and 3D sketching at Speculative Realities Lab

At the Digital Neurosurgery seminar led by Prof. Thomas Picht this week and the next, we had the pleasure of hosting a demo by the software editor BrainLab. One of their researchers visited us at the Speculative Realities Lab, bringing along crates of high-tech gear. He presented to the students, and later to the staff, how the mixed reality could play in their Suite. Using Magic Leap AR glasses, a group of seven could explore a brain data set through the Elements neurosurgical planning software suite: a head of a patient with colorful tracks running through the white matter was suddenly floating in space. They multiplied, as students were invited to play around in the room with them. They could manipulate them by poking at them with a virtual laser.

This tool is introduced as a way to plan surgery, yet also as a powerful pedagogic tool for medical students. I could have a look at the questionnaires filled up the next day by the students and they highly appreciated the experience overall, most of them find it a useful addition to the program —an additional modality into the “anatomical intermediality” of medical training (Hallam 2020). The appeal of 3D images is used as a prestigious mark of futurity.

“Students ‘engage in reshaping their experiential world’, learning specialised vocabularies along with ways of seeing and acting that, it is argued, reconstitute persons – whether living patients or dead bodies – as ‘object[s] of medical attention’ ”

In the next room, on the other side of the wall, I was organizing a very rudimentary 3D sketching workshop using the commercially available app Gravity Sketch. The students ended up creating collaboratively a fuzzy scene, with a parrot and a palm tree, and lots of other scribbles.

This was a lot of fun, and curiosity spread as they were exchanging the headset to share what they had created with one another. The students reminisced about the white matter tracts that they had just seen on BrainLab. This same type of eye candy makes the neuroanatomy mixed reality application look so futuristic and appealing. 3D lines become a kind of play dough and the engagement was obviously higher than with the neurosurgical software. We concluded that combining both of these setups, a joyful interaction together with serious neuroanatomical content, could lead us to an even more potent pedagogical experience. During the next session, we explored the visual power in action in the digital image and how they shape medical practices (Burri 2013). We explored the multifarious ambiguities lurking underneath the apparent opposition between the “beauty” of an image and its “objectivity.” The conversation elevated as we went through a strange case: how and why is it that a medical practitioner can call a tumor “beautiful”? It feels like eye candy comes in many brands and many flavors.

Awake Surgery as Fieldwork: snippet from the "Sketching Brains" participant exhibition project at Charité Berlin

Awake surgery has been a hot spot of neurosurgical research and a growing site of interest for journalists and scholars. The idea is simple yet radical. The patient has a tumor that lies close to the “eloquent areas.” Removing this tumor puts at risk their cognitive abilities, in particular those related to speech. Instead of waiting for them to wake up in order to assess potential damage, which may then be irreversible, why not keep them wide awake during the process, and simulate with low-current electricity the effect of potential lesions on the brain? The result is a very atypical surgical situation with a speaking patient, a patient which is aware of what is happening in the room. This calls for a mastery of the atmosphere around the patient, an atmosphere that requires perfectly rounded-up teamwork to even out possible stressful situations. Here is a draft of one of the graphic ethnographic “series,” that I am presenting in the “Sketching Brains” participant exhibition at Charité in Berlin.

Credit MLC

That morning as I follow Katharina Faust to the OR, she tells me about the “very big tumour” she will have to expurgate from the patient’s brain. The patient is an artist. The OR is quiet, that particular patient seems quite sedated. Katharina bends over the patient, and with a very soft voice, greets her and asks her how she’s feeling today. Mehmet Tuncer, a junior resident who will be stay in contact with the patient during the whole operation, is already at her side. He has already built a relation of trust with the lady? The sounds are ushed and the movements are quiet.

Credit MLC

Three students are in the room this morning: the OR keeps it character of theater and it is very usual to have a small audience for the neurosurgeons at the University Hospital of Charité, which is the leading training center in Germany and in Europe. A few more signatures for Katharina, who seems to be signing papers all day, even a few away from a feat of surgical mastery.

Credit MLC

The skull of the patient is held into a metal clasp, between two dented spikes, as in any other neurosurgical intervention. What is usually a routine affair of a few seconds take longer when the patient is awake, as this is one of the least comfortable feature of the intervention: feeling one’s head stuck into a jaw of steel. A decent amount of local anesthetics makes it a bit easier. The instrument is shown to the patient to reduce her anxiety, with a few sympathetic words.

Credit MLC

A little electric trimmer buzzes in the hands of Katharina as she clears the space where she will incise the scalp. At the site where the outside world is about to smuggle in, a generous spraying of antiseptic solution is keeping the danger of a bacterial incursion at bay.

The head of the patient is also “registered” for the virtual representations of the screen to match with the actual body. A stereoscopic set of cameras is helping the system keep track of the scene, orienting itself of the bearing of the four balls assembled into a cross. On the three big screens of the OR, the scans show the bulky tumour in dark, dangerously close to the colorful lines hinting at the presence of language tracks pathways in the connective tissues of the white matter.

Credit MLC

When the trimming is done, Dr Faust covers the patient’s head with adhesive blue paper protections. Only the site of the craniotomy will be apparent from this side. On the opposite side of the bed, an assemblage of machines has taken over part of the vital functions of the body for the length of the operation.

Credit MLC

My tablet is running out of battery. The last image I can sketch is in the middle of the langage mapping: as Katharina is touching the brains with a pair of electrodes, triggering a temporary inactivation at a determined point, Mehmet is showing to the lady a set of images. Every time Mehmet says “anomie,” it means that the word, like “hand” or “cat,” came out wrong from the patient’s mouth. Katharina then duly puts a numbered piece of paper on the area she just probed, and registers it into the machine with a long pointer. Another round of images focuses on actions. This series of linguistic tasks, coming straight from neuroscientific experimental processes, makes it possible to assess if that specific part of the cortex is critical to the speech functions. The lady is getting tired, but the key information is in. The resection can start! It’s a impressive moment which I won’t be able to render today in the graphic form, as my iPad calls it a day. Next operation is two days, later. That’s exciting!

Conference-as-fieldwork: EASA 2022 in Belfast

So happy to be in Belfast for a dip into our fleshy community of scholars! Ethnographers can’t help it, they attend conferences ethnographically. Here is a graphic report.

The ethnographer at work.

Sitting in the corner that will offer the clearest picture is more often than not a deliberate choice.

Teaching-as-Fieldwork: Open Design studio course "Growing Senses"

The Open Design Master students are moving forward on their Laboratory Project, with the common topic of »Growing Senses«. Laboratory Project is the main studio teaching of the third semester of this program between the Faculty of Architecture of the University of Buenos Aires and the Institute for cultural and media studies of Humboldt University. As the mid-term presentations are approaching, I sat with my colleagues designer Frank Bauer and architect Bastian Beyer for a feedback round. Many projects are emerging: we are joining them to design shape-shifting shading devices, protocols for sensing emotional territories, outer heart fountain flows, plant ritual accessories for extra-planetary life, mycelium spatial collaborations, and garden-based divinatory systems.

“In the classroom as in the field, anthropology demands an openness to encounters with the unexpected, a disposition to the moment and its surprises, their unpredictable knocks and occasional gifts.“ (Pandian 2019, 67)

This is a quick graphic report, straight from my fieldnotes.

Closing an Exhibition-as-Fieldwork #TAT #StretchingMaterialities

The half-year duration of the research process-based Stretching Materialities exhibition at Tieranatomisches Theater has come to an end. The last weeks were full of events, contrasting with the sluggish covid vibe that has plagued most of the exhibition. The pandemic did not seem to restrain much from the experimentation itself, however. Having a public yet intimate place to work, with opening times and visibility, translated into the strong sentiment of having a hub ready for docking new fast-paced projects, such as the Stretching Senses School, or the multiple performances and talks that bloomed nearing the end of the event. What is an exhibition-as-research? The multifarious experimentations to relate space to objects-in-process is part of what “curation” meant in the first place.

“In the seventeenth century Robert Hooke, we might note, was the Royal Society’s first curator of experiments. (The word ‘‘curator’’ was first used to refer to an officer in charge of a museum collection around the same time as the founding of the Royal Society.) Furthermore, the world’s first university museum – the Ashmolean, which opened its doors in 1683 – was also a venue for the public demonstration of scientific experiments.” (Basu & Macdonald 2007, 2)

Experimenting with space, things, and people, the exhibition is an alchemical lab for the making of atmospheres conducive to astonishment, wonder, and knowledge. Bringing the right colors and the right arrangement together, under the right light, with the right timing, and with the right story, curating is an art and a science, as well as a boundary method where scientific and artistic disciplines can overlap and feed each other. Hosting a successful feast isn’t an easy feat: trial and error are part of the investigative endeavor.

Was it an exhibition-as-fieldwork or fieldwork-as-exhibition, or just exhibition-as-place-of-work perhaps? Twice during the last week, a team of DJ and VJ had a gig at the center of the exhibition space, with micro sounds and images captured from the environment: the performance »Scattered Diffusion« by Mascha Kobylenko & Siamend Darwesh was a perfect illustration of the concept of the exhibition. A portable microphone and a smartphone with a microscope add-on were handed out to the participants, wirelessly feeding the node-based mixing software of the two artists standing in the middle of the rotunda. The central round sky-light appliance served as a round projection screen for the images of textile, stone, hair, and many other textures explored by curious hands. Mascha was part of the five mediators that were hired to process our unruly research processes and help make them digestible to the visitors. Soon, members of that team came to us with new ideas for participative performances and installations. They participated in stretching the exhibition space and playing around with the boundary conditions of our curatorial experimentations.

The previous week, Clemens and Skander were setting up the ultimate phase of the microbiological air sampling, a microperformative installation to which the visitors contributed with body particles and dust from their own habitats. Among other atmospheric phenomena, including a much-photographed artificial cloud, the “Algorithmic Weathering” installation of Clemens Winkler is demonstrating the permeability of the exhibition space to the outside atmosphere. The captured invisible population of airborne beings would flourish later as a bacterium culture. They will be archived and exhibited again.

After a relaxing closing event on March 4, the team met for the last time in the exhibition space to have the final setup documented. It was anticipated that the exhibition would be complete only on the last day. The long maturation of the concepts and their weathering through countless tours and modifications has enriched considerably the flavor and scope of our initial schemes.

The professional video artist Ümit worked his magic on our us and our exhibits, shooting “hero” portraits of the curators in the hanboks of Yoonha Kim. “I am a professional, I do everything,” said Natalija as she reluctantly accepted to appear in the video. Acting as being busy on the stage where we have been occupying ourselves for so long didn’t feel so odd: in fact, that felt like a theatrical process coming to fruition, with the “money shots” popping up naturally as they have been rehearsed and performed many times. Exhibition-as-research is a messy method assemblage based on the performative aspect of any science of the real, as John Law would have it.

“Method assemblage, we are learning, needs to be about more than representations. But eitherway – whether we are talking about representations or objects, it becomes clear that truths are not the only arbiters. In an ontological politics we might hope, instead, to interfere, to make some realities realer, others less so. The good of making a difference will live alongside – and sometimes displace – that of enacting truth.” (Law 2004, 67)

As I have learned from co-curating Stretching Materialities, that task boils down to letting the stories we want to tell show us how to tell them, and tell them many times until a robust and faithful one takes hold of the place.

Note to self on performing fieldwork: Vincent Moon's Live Cinema @SomaArtBerlin

For my generation, Vincent Moon is an important image-maker. Part of the Blogothèque team, he was at the forefront of music videos, shooting amazing international bands and solo musicians as they were staying in Paris, while on tour. Shot in intimate settings or while walking in the scenic streets of the French capital, he brought a distinctive craftmanship touch and new freshness to documenting musical artists which immediately seduced the audience of the first social media addiction waves. My wife was born and raised in Valparaiso, Chile, and she has also known the work of Moon since an early age. The video artist started to travel with his camera to capture musical moments in various exotic places, still under the banner of his “take away shows”. This part of his work continues to grow in order and magnitude, as illustrated by the mind-blowing recent collaboration with the Icelandic composer Olafúr Arnalds, “When we are born.”

Vincent Moon is already in another place, however, and he has shifted level over the years. The subsequent period of his work turns to document healing ceremonies and rituals around the world. With his project Petites Planètes, Moon collected an impressive scope of sound, music, and video work, that are available through his label. The quality and the depth of his material would make any visual anthropologist blemish and reach for academic excuses.

Last week in Berlin, Moon presented his material in an audacious performance installation at Soma Art, an underground art space in Wedding.

The artist was VJing his own material, producing a soundtrack to a collage of his now-familiar footage. The exhibition space, with its industrial high ceiling, freshly painted in white, was vast and inviting. Young kids were running around, letting the parents sip red wine and delve into the colorful universe of Moon’s travel. A few cushions, benches, and a colorful carpet were enough to provide a cozy feeling to the audience. The delivery of the performance, quite in tune with the material, was devoid of false pretends. Jumping around like a house DJ, Vincent Moon was visibly feeling at home with his crowd, his pictures, and his soundscapes. This playful and lively way of showing footage of initiation and healing ceremonies came across as an honest manner to convey a creative and spiritual journey and share it with the public. Not a devilish “tour de force”, but a straight-forward “tour du monde” and a simple message of inspiration and creativeness, shedding sunlight through the icy rain of Berlin’s darkest moment of the year.